Dr Yap also identified another sea anemone that we have been seeing, and reassigned a commonly seen anemone into another grouping.

From Dr Nicholas Yap's awesome paper: Taxonomy and Molecular Phylogeny of the Sea Anemone Macrodactyla (Haddon, 1898) (Cnidaria, Actiniaria), with a Description of a New Species from Singapore. Zoological Studies 62:29 (2023) doi:10.6620/ZS.2023.62-29. Download the pdf

Macrodactyla fautinae is the anemone we fondly call the Tiger anemone - because it has stripes and is seen to fiercely eat things bigger than itself! Like sea pens. The pale body column has rows of perforated red-tipped bumps. With its tentacles tucked into its rounded body, the anemone looks like a bizarre strawberry - so we sometimes also call it the Strawberry anemone. The anemone is often seen to protrude a large portion its 'throat' out of its body. Sometimes, so extensively that its tentacles are hidden and it appears to be a blob or jellyfish. Dr Nicholas Yap comments that perhaps it is this behaviour that allows it to capture large prey!

This sea anemone is particularly meaningful to me. It was among the first anemones we showed to Prof Daphne. I was terrified when the museum first asked me to bring her along on our surveys. Prof Daphne is the world authority on sea anemones. She has seen anemones from the deepest oceans, from remote islands, anemones from everywhere. Would our shores be boring for her? The first shore we were scheduled to survey with her was Changi opposite the SAF chalets at Changi Creek on July 2007. When we showed her the Tiger anemone, she declared that she has never seen it before. Wow! After that, I felt more confident about Singapore shores, and about sharing them with scientists.

|

| Our first trip with Prof Daphne in July 2007 |

|

| Prof Daphne enthralling student volunteers during the Comprehensive Marine Biodiversity Survey Oct 2012 |

|

| Prof Daphne pointing out anemones on Sister's Island, during a regional anemone workshop in Jun 2011. |

What is the fate of the Tiger anemone?

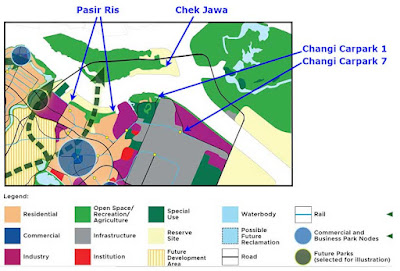

The newly described Tiger anemones are quite commonly seen on Changi beach from Changi Creek to Carpark 7, and sometimes on other Northern shores. But so far, we have not found them in the South, except once at Cyrene. With scheduled reclamation at Changi, will we lose these sea anemones forever?

In the Long-Term Plan Review, there doesn't seem to be a change in 2013 plans to reclaim all of Pasir Ris, all of Changi from Carpark 1 to Carpark 7 and beyond, and reclaim Chek Jawa and Pulau Sekudu. Including plans for a road link that starts at Pasir Ris, crosses to Pulau Ubin, right across Chek Jawa to Pulau Tekong, and back to the mainland at Changi East.

See the Tiger anemone and Changi shores for yourself before they are gone!

Changi shores are easy to get to, and enjoyed by many people. But it remains rich in a variety of marine life. More details in "Changi - an easy intertidal adventure for the family".

|

| Changi has lots of other kinds of sea anemones too including very large carpet anemones! |

Thanks to Ang Qing for featuring this and other sea anemones

Ang Qing Straits Times 21 Aug 2023

SINGAPORE – Resting in plain sight in the sands off Changi’s coastline, a sea anemone that looks like a pale strawberry was identified recently by local scientists as a species new to science.

Findings on the tiger anemone – so called because of its stripes and ability to swallow prey larger than itself – were published in the scientific journal Zoological Studies.

While the creature has been noted by marine life enthusiasts since the 2000s, sea anemone researcher Nicholas Yap took about a decade to conclude that this species is like no other.

The 39-year-old research fellow at St John’s Island National Marine Laboratory told The Straits Times: “It’s such a chaotic group of animals and everything looks similar.

“I remember when I was in the National Museum of Natural History in Paris in 2019, I looked through the shelves (where other anemone specimens are stored) for two weeks just to make sure that nothing looked like this anemone.”

Confirming it was a new species involved genetic analysis of samples and poring through hundreds of specimens in museums across the globe.

The study was co-authored by researchers from the Museum of Tropical Queensland and the National University of Singapore.

The animal’s scientific name, Macrodactyla fautinae, is a tribute to one of the world’s leading authorities on sea anemones – the late Professor Emerita Daphne Gail Fautin from the University of Kansas, who was undecided on the species’ identity during her visits to Singapore.

The tiger anemone is just one of several species that Dr Fautin could not identify, said Dr Yap, who aims to continue his mentor’s work in describing anemone species.

Dr Fautin and Dr Yap helped discover the brown peachia anemone (Synpeachia temasek) in Changi, which is also unique to Singapore

Recounting Dr Fautin’s involvement in expeditions to survey the Republic’s marine biodiversity, marine enthusiast Ria Tan described the zoologist as a “very patient teacher who was always in a good mood during morning surveys”.

“She gave everyone a chance,” said Ms Tan, who is part of Singapore’s Anemone Army, a moniker coined by Dr Fautin for a group of citizen scientists who help collect specimens of the animal.

The scientists involved in the study also decided to name the pink-spotted anemone after Dr Fautin because it is similar to another anemone with pink dots that she had named after her husband, Dr Robert Buddemeier.

While the tiger anemone is rather common in the Changi area, it has not been seen elsewhere, which warrants further research, said Dr Yap.

Much remains unknown about sea anemones, he added.

Anemone expert Meg Daly of Ohio State University said: “Broadly speaking, the tropics are perceived as relatively less biodiverse for sea anemones, compared with temperate regions and polar regions.”

This is probably because scientists who have studied sea anemones were or are usually based in temperate regions, she said, noting that biodiversity is not as well documented in the Indo-West Pacific, and as a result, names of sea anemones from elsewhere in the world may be used incorrectly.

Professor Daly said the tiger anemone is an unusual finding in the 21st century as it is a large-bodied anemone in shallow water.

“More commonly, the new species we are finding in the 21st century are smaller bodied, otherwise cryptic, or living in habitats that are very inaccessible,” she noted.

More than 1,000 species of sea anemones have been identified around the world, and there is a growing body of work done to understand their toxicity and potential for uses in medicine and novel materials.

Dr Yap, who also studies jellyfish, which are relatives of sea anemones, said: “A lot is still unknown about the venom of sea anemones and jellyfish. Knowing which anemone has stung a person helps find which treatment is effective.”

For instance, while vinegar is known to be useful to treat box jelly stings, it is not useful for other jellyfish, like the portuguese man-of-war, which can deliver painful stings too, said Dr Yap.

Researchers are also looking at how sea anemones adapt to climate change as the sea warms.

Dr Yap said: “So far, we’ve seen some evidence that some sea anemones have colonised spaces where corals once thrived on Kusu Island, preventing younger corals from establishing themselves.”

More than meets the eye

Singapore’s researchers made another marine life-related discovery in May.

They found that Pteraeolidia semperi, a nudibranch or sea slug more commonly known as the blue dragon, is not a single species but many genetically distinct species that look similar.

This was sparked by Yale-NUS College graduate Nathaniel Soon’s encounters with different variations of the brilliant sea slug across the region and in Singapore’s waters.

It left him puzzled and determined to study them for his final-year project at Yale-NUS, where he pursued environmental studies.

His findings were published on May 31 in the Journal Of Molluscan Studies.

Within Singapore, researchers have discovered at least two lineages of the blue dragon from samples collected from offshore sites, including the Cyrene Reefs, Pulau Hantu and Pulau Semakau.

Mr Soon said: “Nudibranchs function as essential indicators of ecosystem health – an area with a wide variety of nudibranchs may suggest thriving and resilient reefs.”